Throughout the last decade, the UK government has missed several opportunities to hedge future energy prices by supporting a more rapid deployment of renewable energy under the Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme.

During the 2021/22 energy crisis, when gas prices went skyward, the government’s timidity cost the UK consumer several billions, which would have otherwise been saved via CfD negative payments from renewables generation which, alas, had not been built.

With the parameters for the CfD Allocation Round 6 (AR6) now announced, once again the government is lagging behind the market. This means that, if we have another energy price spike, consumers will again be exposed to higher electricity prices.

In previous posts, Regen has highlighted the opportunity that CfDs provide to hedge against rising energy prices. At that time, there was a broad consensus across industry and consumer groups that government should expand and accelerate the use of CfDs to bring forward new energy projects and potentially even allow existing generators to enter into a CfD-type contract.

CfDs as a hedge against future energy prices

For those unfamiliar with the CfD scheme, the basis of the revenue support mechanism is a two-way payment against an agreed ‘strike price’. It’s two-way as, if the electricity wholesale price is low, the generator receives a top-up payment paid for by consumers, but if the wholesale price is high, the generator makes a payment back to consumers via the electricity levy.

In the period from 2013 to 2020, which saw high CfD strike prices and low market prices, the payments flowed to the generator as a revenue subsidy. But since 2021, which much higher wholesale prices and lower strike prices for new projects, the payment flows have regularly been in the favour of consumers. This negative payment reached a peak during the energy price crisis of 2021 and 2022, when the CfD payments strongly favoured consumers.

The lesson, which seemed to be obvious, was that the government could effectively hedge against higher future electricity prices by entering into a risk-sharing deal with lower-cost renewable generators, and in so doing help to achieve the UK’s net zero energy strategy.

How to fluff an allocation round

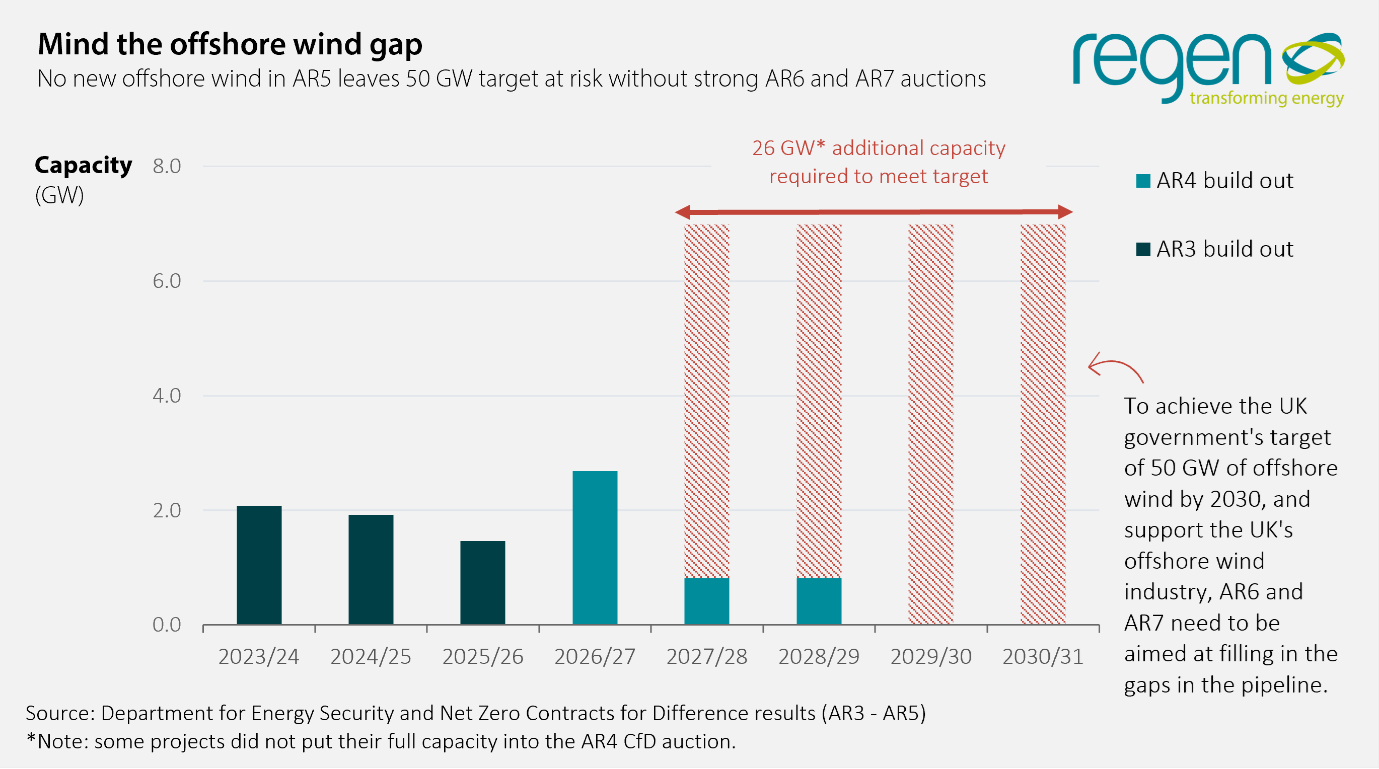

It should have been all systems go for an accelerated rollout of renewable energy, but almost immediately the government made a misstep by setting the Administrative Strike Prices (ASP) too low for AR5. This meant that, although onshore wind and solar did well, the auction received no bids from offshore wind and a big gap opened up in the offshore pipeline.

Roll on to AR6. Another year passes, with some good news that officials have worked with industry to come up with a more realistic ASP for offshore wind at £73 per MWh in 2012 prices. A price which better reflects the rise in supply chain and construction costs. The auction budget set at £800m per year is also reasonable and a big step up from AR5 (£170m). Here we go!

But oh no… government has set the auction’s Market Reference Price (MRP) at only £24.13 per MWh in 2012 prices, which equates to around £33 per MWh in today’s prices. I’m not sure what market the government is thinking of, but no-one is buying electricity at that price today and no-one expects electricity prices to fall to that level at any time over the decade. This calculation seems totally outside any market expectation and any reasonable forecast.

The reason that this little parameter is so important is that the budget MRP is the price that government uses to calculate the budgeted cost of the CfD scheme. In other words, if they assume a bizarrely low MRP, the forecasted CfD payments will always flow in favour of the generator and the auction budget will quickly be expended. The result is that an auction that might be expected to support 8-10 GW of new offshore wind, because that is what is needed, is only going to support 3-5 GW.

The industry is now asking a lot of valid questions. Why did they set the reference price so low? Is this a mistake? On what basis was such a calculation made?

The cynics are concerned that, although government wanted to announce a record budget to grab headlines (“record support for renewable energy”, as it appeared in the Financial Times), in fact they are still firmly wed to the idea that renewables are expensive and are therefore dragging their feet on net zero. The more cynical cynics are also suspecting that the current government didn’t want to do anything that might help a future Labour administration reach its net zero targets.

Either way, the upshot is that we will build less offshore wind than we might otherwise. Treasury may think it has saved money and reduced borrowing, but in reality the consumers may well end up paying more for electricity if wholesale prices rise again, not to mention the economic growth and net zero benefits that are foregone. Unfortunately, as is the way with many policy decisions, when we look back and say this was a mistake, ministers will have moved on.

With the parameters for the CfD Allocation Round 6 now announced, once again the government is lagging behind the market. Here Regen director Johnny Gowdy argues that, if we have another energy price spike, consumers will again be exposed to higher electricity prices.