As the leadership of the UK changes, this is an opportunity for the new Prime Minister, or Energy Minister, to make significant reforms towards decarbonisation. One of the highest priorities should be to change Ofgem’s statutory remit to include decarbonisation as an objective, for example, by linking Ofgem’s outputs to the interim targets set by the Climate Change Act 2008 and any subsequent update to those targets as a result of the government’s net zero commitment.

This would allow Ofgem to:

- consider, report and account for the decarbonisation impacts of regulatory change, investment guidelines and other activities

- allow network operators greater flexibility to recognise and to act upon regional energy priorities and objectives when setting investment guidelines and reviewing evidence

- establish a framework to assess the value of investments to deliver short-term carbon savings, as well as fitting with long-term decarbonisation pathways.

There has been a lot of discussion in recent months about whether Ofgem’s mandate allows it to give sufficient weight to environmental protection, and in particular to the delivery of the UK’s decarbonisation targets. The Guardian has this week carried another article which features calls from the CBI for the regulator’s mandate to be updated, or risk sending “negative signals” to investors in low carbon technology. This Guardian article mirrors concerns that have been raised by industry analysts that the regulator’s mandate is now seriously out of date, and needs to be radically changed to put decarbonisation, and the new imperative to achieve a net zero carbon target, at the heart of energy policy.

It may not seem immediately clear how important it is for decarbonisation to be an explicit objective for Ofgem until one considers just how broad and far-reaching Ofgem’s role is, in comparison to other regulators. Ofgem’s leadership in the management and evolution of the energy system ranges from overarching strategy, to the minute detail of industry codes – with such direct involvement, carbon reduction must be an explicit objective at every stage.

Ofgem itself appears to at least acknowledge that change is needed, although it has not yet publicly called for a change to its terms of reference. In a recent speech by economist and Ofgem chair, Martin Cave, there was a clear recognition that the role of Ofgem needs to change with decarbonisation having a far greater prominence:

Ofgem has an important role in the way we administer the Government’s renewable and energy efficiency schemes and regulate the energy market in minimising the costs of the low-carbon transition. The decisions over how we change the gas and electricity network and create markets for new flexible solutions will be fundamental in ensuring efficient low carbon energy use. Ofgem’s role in assessing the trade-off between current and future consumers’ interests – between cheaper prices now and more sustainability – will come into greater prominence. …in these new circumstances we will probably have to take a more active role in building Great Britain’s low carbon energy system – in the interests of future consumers.

Martin Cave, Chairman, Ofgem

This theme of giving greater weight to decarbonisation, and to the benefit of future consumers, has been taken up in Ofgem’s Strategic Narrative 2019-2023.

It is not clear however whether this change in emphasis will translate into any significant change in the regulator’s actions. Especially since there seems to be a very strong and enduring belief within Ofgem, that its role to support decarbonisation is limited to creating a level playing field for all technologies to compete, and by driving down energy costs, making the transition more acceptable to the consumer. There is also the view that proactive policies to accelerate decarbonisation, or otherwise support low carbon technologies, must originate with actions taken by government not the regulator.

Meanwhile the government’s view seems to be to avoid making any policy changes. At least that is the impression that has been given by the energy minister, Chris Skidmore, in response to a Labour parliamentary question, as he poured cold water on the idea of any new mandate and merely pointed to the energy acts of 1986 and 1989 as evidence that Ofgem has sufficient remit to address environmental issues.

Ofgem’s mandate on decarbonisation (and energy devolution) needs to change

Regen has worked closely with Ofgem on a number of consultations and policy engagements and, while we have some sympathy with the view that energy strategy ought to originate from Whitehall, we believe that role of the regulator is too important, and the potential for poorly-considered regulation to delay decarbonisation is too great, for it maintain a neutral position on decarbonisation.

In recent months Regen has highlighted areas which we believe Ofgem’s regulatory position, and lack of a firm decarbonisation objective, is inhibiting the low carbon transition. These include the regulatory changes to reduce embedded benefits, the minded-to outcome of the Targeted Charging Review, and the lack of firm decarbonisation objectives within the RIIO-2[1] price control framework.

A more fundamental limitation of Ofgem’s current approach is that the regulator seems wedded to the idea that investment in anything that may not be necessary to meet a 2050 target is, by definition, a regret cost. This misses the critical point that mitigating the impact of climate change is about managing risk, and in any risk analysis there is a benefit, and a strong economic case, to decarbonise as quickly as possible to limit the escalating impacts and costs on future consumers.

There is also the need, as the Committee on Climate Change has pointed out, to “act now to keep long-term options open”. This means making investments in the short-term, even at the risk of incurring short-term costs, because:

- Mitigation of climate change is about managing an increasing risk. The more CO2 emitted the greater the risk of reaching tipping points and incurring far reaching and unknown impacts.

- There is a need to support the development of new markets to enable cost reduction, as has been proven by the success of offshore wind.

- In the case of heat, even in the long term there will probably continue to be several technology solutions which will be applied for different use cases.

- Delays on decarbonisation – meaning more cumulative carbon is emitted – will require more drastic and therefore costly actions in the future.

As well as decarbonisation we would ask that any review of Ofgem’s mandate should also consider the needs of a more devolved energy system by allowing greater governance and decision making at a regional level. There seems to be an inherent contradiction for network operators to be required to consult and engage with regional stakeholders, but then be prevented from taking action because of a very centrist regulatory framework. Instead, there is a strong case that network investment needs to reflect the priorities and strategies of regional stakeholders.

If network operators are prevented by the regulator from reflecting local energy priorities in their business plans, it is understandable that stakeholders may conclude that the engagement has not been genuine and that network operators are to themselves blame. This perceived lack of responsiveness to local need has now become a significant issue and is one of the factors fueling the argument for re-nationalisation.

RIIO-2 Guidelines do little to support network decarbonisation

As an example of how the regulatory framework is preventing investment to support decarbonisation, we would highlight the Ofgem RIIO-2 guidance documents that have been issued to electricity and gas network operators to inform their business planning ahead of the next price control period. Since RIIO-2 will determine both the level of network investment and the “outputs” that this investment must deliver, the impact of these guidelines could be significant.

As an example, Section 3 of the RIIO-2 Sector Specific Methodology Decision – Gas Distribution, which deals with environmentally sustainable network outputs, sets out some pretty far-reaching guidelines to determine which proposals for gas distribution network investment are taken forward.

Whereas we might expect that this section of the guidelines would reflect the urgency to decarbonise heat and the critical role that can be played by the gas network, the message from Ofgem is in fact very cautious to the point that it seems to be actively discouraging decarbonisation investment proposals.

Instead Ofgem’s conclusion is that, in the absence of a long-term strategy, gas network operators should not invest in any material way to try to achieve a particular decarbonisation outcome. Or as the guidelines state:

“One of the biggest environmental challenges facing GB is how best to decarbonise heat. Ongoing uncertainty around the UK’s decarbonisation pathway means it would be premature for GDNs [gas distribution network operators] to begin making material investments in anticipation of a particular scenario.”

Ofgem reinforces this point by not creating any specific heat decarbonisation output (objective) for the networks to achieve in their business plan;

“we will not create a specific heat decarbonisation output. This is because the role of gas distribution in heat decarbonisation is too uncertain to specify an output at this time.”

There are exceptions to the general ‘do nothing’ advice – no or very low regret investments, aligned with business-as-usual outcomes and meeting a very high cost-benefit[2] hurdle, can be proposed. There will also continue to be an innovation stimulus pot to support first of a kind investments to trial new solutions, although it is not yet clear how sizeable the pot will be.

It is understandable that network operators have interpreted this guidance as a clear steer against making investment proposals within their RIIO-2 business case to support decarbonisation, for example, to support increased levels of biomethane injection or future hydrogen networks. With the RIIO-2 price control period ending in the late 2020s, that takes us very close to the 2030 deadline given by the IPCC to limit the worst effects of climate change.

Paradoxically, Ofgem’s “no regret” guideline does not seem to extend to investments that would extend or continue the use of fossil fuels. There is no reference, for example, to the stated government policy to introduce a future homes standard mandating the end of fossil fuel heating systems in all new houses from 2025.

case study

Case study: Biomethane grid injection – a regional opportunity that could be hamstrung by lack of network investment

As a specific example of where this will have a direct impact, Regen has been looking at the potential growth of biomethane injection into the gas network.

Biomethane has been identified by the Committee on Climate Change, DEFRA[3], Treasury[4] and by a host of devolved government and regional stakeholders as a significant opportunity to decarbonise, to reuse waste and to create new jobs and revenue streams within the agriculture and food processing industries.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has gone further to identify that biomethane will be a key technology enabler to achieve a net-zero target by 2050[5] with a suggested national target of 20 TWh[6] of annual injection to the gas networks by 2030.

“Low-carbon heat. Detailed plans should be published to phase out the installation of high-carbon fossil fuel heating in homes and businesses in the 2020s, ensuring there is no policy hiatus in 2021. Further action is needed to deliver cost-effective uptake of low-carbon heat. Cost-effective and low-regret opportunities exist for heat pumps to be installed in homes and businesses that are off the gas grid, together with low-carbon heat networks in heat-dense areas (e.g. cities) and for increased volumes of biomethane injection into the gas grid (up to around 5% of gas demand). “ Committee on Climate Change

Biomethane is also a good example of a regional energy and industrial priority. Given their strong, rural economies, both the South West of England and Wales have identified biomethane production and network injection as a potential opportunity to not only decarbonise the agriculture sector and utilise waste resource, but also to deliver economic benefits. It is no surprise therefore that biomethane has featured as a hot topic at our stakeholder engagement events and during our evidence gathering when looking at regional energy and industrial strategies.

Regen’s work with the Institute of Welsh Affairs to develop an energy vision for the Swansea Bay City Region identified biomethane as one of five key strategic opportunities for the region, and for Wales. Similar regional arguments could be made for hydrogen in the north of England, wind energy in Scotland and Wales, solar PV in Cornwall as well as heat pumps and EVs in many cities.

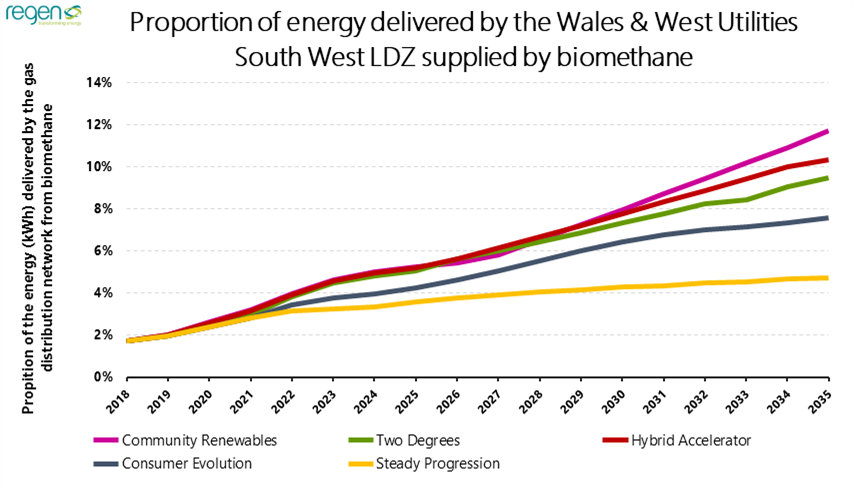

In the South West of England it is estimated that biomethane injection from 18 connection sites has already risen to provide 1.7% of the gas network’s annual energy. This is significantly higher than the 0.4% national average and reflects the strong uptake of biomethane production in the region particularly from agriculture and energy crops. It also reflects the emphasis and support that biomethane has received from the region’s stakeholders, including the Local Enterprise Partnerships, food and agricultural sectors.

Based on the region’s excellent resources and the potential growth in uptake from agriculture and food processing industries, our analysis suggests that biomethane injection in the South West could exceed 10% of network energy content by 2035. With the right policy stimulus growth could be rapid. The 18 sites currently connected are using around one third of their connection capacity and we are aware of another half dozen or more sites that are in the development pipeline. The South West could easily see injection levels rise to 5% of energy delivered by the mid 2020s.

A barrier to growth in the South West, and any other region with the ambition to develop this technology, is that network investment will be needed.

In simple terms, very low levels of biomethane injection (<2% energy content) can be blended into existing network supply with minimal investment. Higher levels of biomethane, especially if concentrated in geographic areas will require more network investment such as smart pressure controls, pumping and compression assets, to supply biomethane to higher pressure tiers and maintain energy density. In addition, additional gas storage could be used to facilitate biomethane injection as an alternative to natural gas.

Such an investment needs to be strategically planned and delivered ahead of need; this could not be supported by individual injection projects. There is therefore a strong case for sharing the cost of facilitating further biomethane injection, reducing carbon emissions from heat and gas in the next decade and beyond.

case study

Recommendation for the next energy minister

If the industry, regional stakeholders and the regulator itself agrees that there is a need for government to provide Ofgem with greater clarity, then the upcoming energy white paper would be a good place to put this in action.

Potentially this could be done by explicitly including decarbonisation as an output of the regulator, for example, by linking Ofgem’s outputs to the interim targets set by the Climate Change Act 2008 and any subsequent update to those targets as a result of the government’s net zero commitment.

This would allow Ofgem to:

- consider, report and account for the decarbonisation impacts of regulatory change, investment guidelines and other activities

- allow network operators greater flexibility to recognise and to act upon regional energy priorities and objectives when setting investment guidelines and reviewing evidence

- establish a framework to assess the value of investments to deliver short-term carbon savings, as well as fitting with long-term decarbonisation pathways.

In the short term we feel it is necessary for Ofgem to quickly update its investment guidelines to network operators ahead of the RIIO-2 business plan submission.

Johnny Gowdy

director, Regen

References

[1] RIIO 2 – Revenue using Incentives to deliver Innovation and Outputs is the price control framework used to regulate the investments, revenues and therefore profitability of energy network companies against a set of agreed outputs. RIIO business plans are set periodically with the next gas distribution and electricity transmission period beginning in 2021 and electricity distribution beginning in 2023.

[2] “…backed by clear justification and appropriate evidence. These projects should focus on activities directly related to the gas network. While there is considerable scope for projects beyond gas networks to deliver low and no regrets heat decarbonisation across society, we do not see a strong rationale for these to be funded by the gas distribution price control.” RIIO-2 Sector Specific Methodology Decision – Gas Distribution, Ofgem

[3] For example see Anaerobic Digestion Strategy and Action Plan A commitment to increasing energy from waste through Anaerobic Digestion issued by Defra in 2010

[4] Chancellor Phillip Hammond’s Spring Statement to Parliament 2019 commitment to “publish proposals to require an increased proportion of green gas in the grid, advancing decarbonisation of our mains gas supply”.

[5] Net Zero The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming Committee on Climate Change May 2019

[6] Page 94 – https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/reducing-uk-emissions-2018-progress-report-to-parliament/

Regen’s director,

Regen’s director,