We need to talk about green tariffs…..

There has been a rapid growth in the number of low-cost green tariffs on offer for renewable electricity. This has been accompanied by a sharp rise in consumers switching away from the “big 6” to take advantage of cheap energy deals, while also doing their bit for the planet. This is great news and an indication that the public, and many businesses, are strongly motivated to go green and support the growth of renewable energy technologies.

Unfortunately, not all green tariffs are equally green. There is a looming greenwash problem which, if the industry is not very careful, has the potential to undo a lot of the good work done to persuade householders and business consumers to make the switch to a greener energy future.

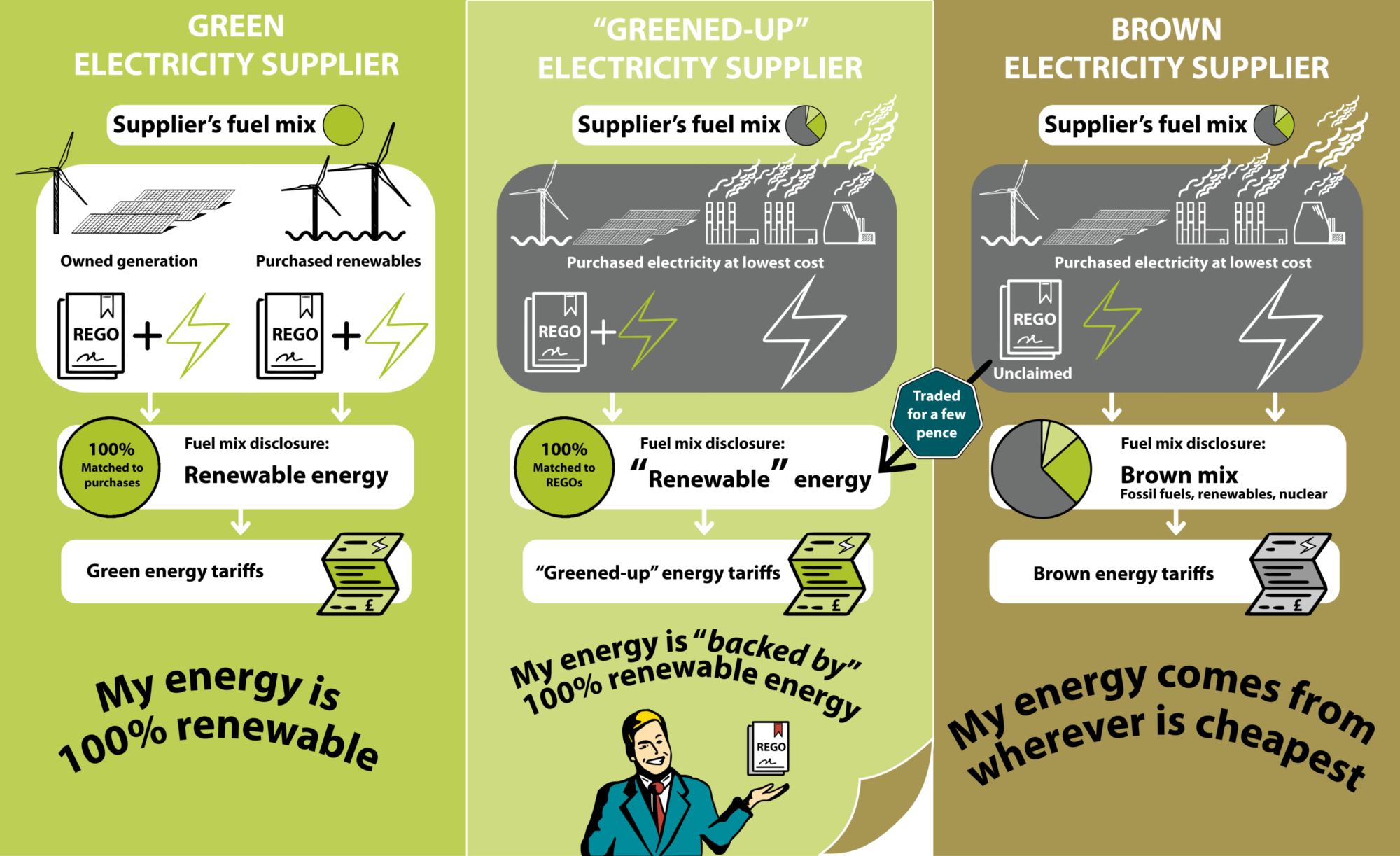

The issue is mired in the murky world of how energy suppliers report their annual Fuel Mix Disclosure and the basis by which companies can then declare their tariffs to be “100% renewable”. Simply put, some companies which offer “green” electricity tariffs can greenwash their brown energy supply by trading Renewable Energy Guarantee of Origin (REGO) certificates in a secondary market, without buying or self-generating the accompanying renewable electricity.

Secondary trading of REGOs exploits a loophole under current fuel mix reporting rules. With REGOs available for just a few pence[1] per MWh, and intense competition to offer a cheap green tariff, it has become very attractive for some companies to buy REGOs, not renewable electricity, for a fraction the value that many consumers place on sourcing their energy from a supposedly green supplier.

Figure 1 Use of traded Renewable Energy Guarantee of Origin (REGO) certificates to “green up” energy supply (infographic by Frankie Mayo for Regen)

Why is this a problem?

Regen believes that the practice of trading REGOs raises three key issues, which are already having a negative impact on the growth of renewable energy and efforts to decarbonise the UK economy.

- Trust – There is a clear risk of mis-selling to consumers who have made a decision to opt for a green tariff and expect that the electricity they consume will be sourced from renewable resources. The likely backlash from consumer groups and regulators could lead to a loss of trust in all green energy products; the good as well as the bad.

- The ability of energy supply companies to green-up their energy supply without buying renewable energy undermines the value chain, which should ensure that a portion of the extra value ascribed to green energy is captured by the energy generator. At a time when renewable energy investment is falling, and small and community-scale projects are struggling to get finance, it is important that every potential source of value is realised. Greening-up energy products by means of REGO trading denies that possibility and erodes the value of future renewable energy generation.

- There is a risk that the practice of trading REGOs will be emulated by corporations and other organisations that want to decarbonise their energy supply. This could undermine the nascent market for green corporate PPAs and other green products which will become an increasingly important source of value for the renewable industry.

Until now, the question about what is and isn’t a green tariff has been largely confined to a heated argument within the confines of the energy supply industry. Recently, however, the UK government’s decision to impose a tariff price cap, and the resulting debate about whether “green” tariffs should have an exemption, has drawn the issue to the attention of policymakers and regulators.

Initially, ministers indicated that the government was minded to support a green tariff exemption. But as the Domestic Gas and Electricity Tariff (Price Cap) Bill made its way through parliament, the debate shifted as policymakers became aware that there is no clear definition of what a green tariff is. Ofgem, in a pretty damning assessment of the value of green tariffs, has stated that it has seen no evidence that green tariffs “could materially support the production of renewable energy over and above what is already in place”. Ofgem’s evidence cited the availability of cheap REGOs, as well as the gaming risk of companies with mixed supply portfolios simply switching renewable energy supply from “brown” to “green” tariff customers without materially increasing the demand for renewable energy.

“We also note that suppliers can buy REGOs cheaply, so it is easy and cheap for suppliers to ‘green’ some tariffs. As such, our starting point is that simply having renewables in the portfolio is not enough to demonstrate that a tariff is providing support for renewables.” Ofgem Default Tariff Cap: Policy Consultation Appendix 13 – Renewable tariff exemption May 2018 https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/system/files/docs/2018/05/appendix_13_-_renewable_tariff_exemption.pdf

Clear definition and transparency needed

The Ofgem assessment is a shame as there are undoubtedly energy supply companies that have a long track record of supporting and investing in the renewable energy sector, and new companies entering the market that are supporting the development of local and community energy schemes.

Having spoken to a number of energy supply companies that genuinely want to be green, there is a strong sense that they would welcome clarity on the rules, and the creation of a level playing field that would enable them to clearly differentiate and honestly sell green energy products. It is striking that the energy supply companies who gave evidence to the committee stage of the “Price Cap” bill are in agreement that there needs to be a clearer definition of what is a green energy tariff and a much more transparent method of fuel mix reporting. The issue for many is that the competition is so intense, and the means of marketing green products so opaque, that, with a few notable exceptions, it is extremely hard for ethical companies to make a stand.

It is very likely that the regulator will be asked to take action on this, as a consumer protection issue if nothing else. Before then, Regen would like to engage with the sector and try to come up with a better, more defensible way to define and market green energy tariffs.

The goal should be to get to the point where consumers will be able to buy green energy with the confidence that their choice of supplier is supporting the growth of renewable energy and the reduction of carbon emissions. The extra value captured by renewable energy (through PPAs for example) will then encourage renewable energy generators to invest in new capacity and to answer one of Ofgem’s main challenges about whether green tariffs do materially add value to renewable generators.

Without wanting to get into too much detail, a couple of obvious changes could be made. For a start, companies should be required to clearly differentiate within their Fuel Mix Disclosure between REGOs that have been acquired through the generation or purchase of renewable energy, and those that have been acquired in the secondary REGO market without the purchase of accompanying renewable energy.

That in itself should be enough to prevent claims that a tariff is “100% renewable”, “backed by 100% renewable energy” or other forms of potentially misleading statements unless the energy purchased and supplied is genuinely renewable.

It is more tricky, then, to define what a green tariff is. We expect that companies that are in many other ways green, ethical and committed to decarbonisation will, for practical reasons, struggle to meet a 100% renewable energy threshold and, if they were required to do so, the resulting price of a “pure green” tariff could exclude some customers.

The issue here is transparency. If we want a green tariff to be available to all customers then some compromise will likely be needed. If an energy company purchases a significant proportion of its energy from renewable generators, and wants to therefore describe itself as a green energy supplier, then they should have the confidence and transparency to declare what their actual fuel mix is.

In addition, companies that do go the extra mile to support renewable energy through other means, such as buying directly from local and community generators, ought to be able to signal their ethical stance to their consumers, but not as a green veneer on an otherwise brown energy product.

Regen will be holding a session looking at the ethical issues facing the renewable energy sector at this years Renewable Futures Conference

Johnny Gowdy is a director at Regen. Regen is a not-for-profit centre of energy expertise and market insight whose mission is to transform the world’s energy systems for a low carbon future.

Renewable Futures and Green Energy Awards

Join experts and key policy makers Renewable Futures and Green Energy Awards 27 November 2018 to examine the disruptive innovations shaking up energy market and the successful strategies to create value in a rapidly changing market.

[1] REGO prices have been around 15p per MWh. So the cost to “green-up” a family bill could be less than 50p per year. The market is awash with unclaimed REGOs as electricity now accounts for 25-30% of electricity sold much of which is sold in the brown market without the need to claim a REGO.