Following a weekend of particularly low wind generation, Regen’s director Johnny Gowdy uses three charts to make the case why the UK should harness the opportunity to expand offshore wind projects in the west of GB.

The past weekend (16th-19th December 2021) has provided a perfect example of why the UK, and Europe, needs to develop a much more diversified wind portfolio, and in particular to expand offshore wind projects in the west of Great Britain, in Ireland and along the western seaboard of Europe.

This is a point that Regen has been making for a number of years, going back to our work to support the Atlantic Array and Navitus Bay windfarms, and the wider development of offshore wind in the English Channel and Celtic Sea. It is one of the reasons why Regen strongly welcomes the Crown Estate’s recent announcement to develop 4 GWs of floating windfarms in the Celtic sea, the Lease Round 4 expansion of wind farms in the Irish Sea and the Scotwind leasing programme.

The argument in favour of more wind in the west, to help balance the UK’s energy supply, increase energy security and reduce price volatility is explained below using three charts.

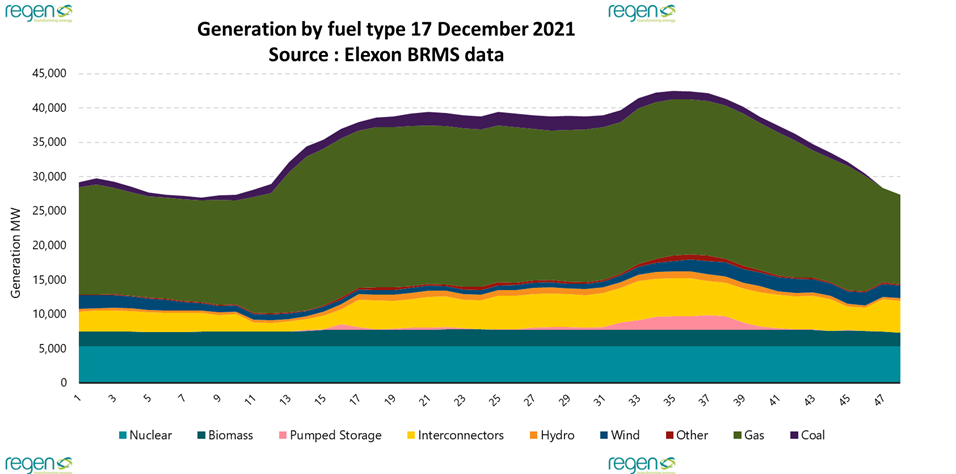

Chart 1 : A high pressure system sits over the southern North Sea, wind generation falls and electricity wholesale prices rise.

The high pressure system that persisted in the North Sea from 16-19th December was accompanied by very low wind generation over a wide area. From Thursday afternoon to Saturday, the High Pressure System sat over the southern north sea centred just off the coast of Hull.

In the summertime, we normally associate high pressure systems with fine sunny weather; in the winter they can also be associated with clearer skies, but there is a variety of high pressure system that is associated with very low winds at its centre and with overcast and foggy conditions, as cold air and moisture is “trapped” beneath the pressure cap. This weather can persist for several days across the southern north sea and into northern Europe bringing still, dank and sometimes cold weather. In Germany this is known as a Dunkelflaute, and it’s not very good for generating renewable energy either from wind or solar.

In Great Britain, on 17th December, wind power output fell at times to less than 1 GW, leading to an increased reliance on gas generation and even some coal. Low GB generation, coupled with lower generation in northern Europe, plus a new problem with French nuclear power and the underlying high gas prices, led to a reduced capacity margin and very high day-ahead wholesale electricity prices.

This was not an extreme event, temperatures were around average, but it was a particularly low period of wind generation (although, it should also be said that the energy system coped well, the lights stayed on, albeit with an increase in gas generation and a short-term price spike).

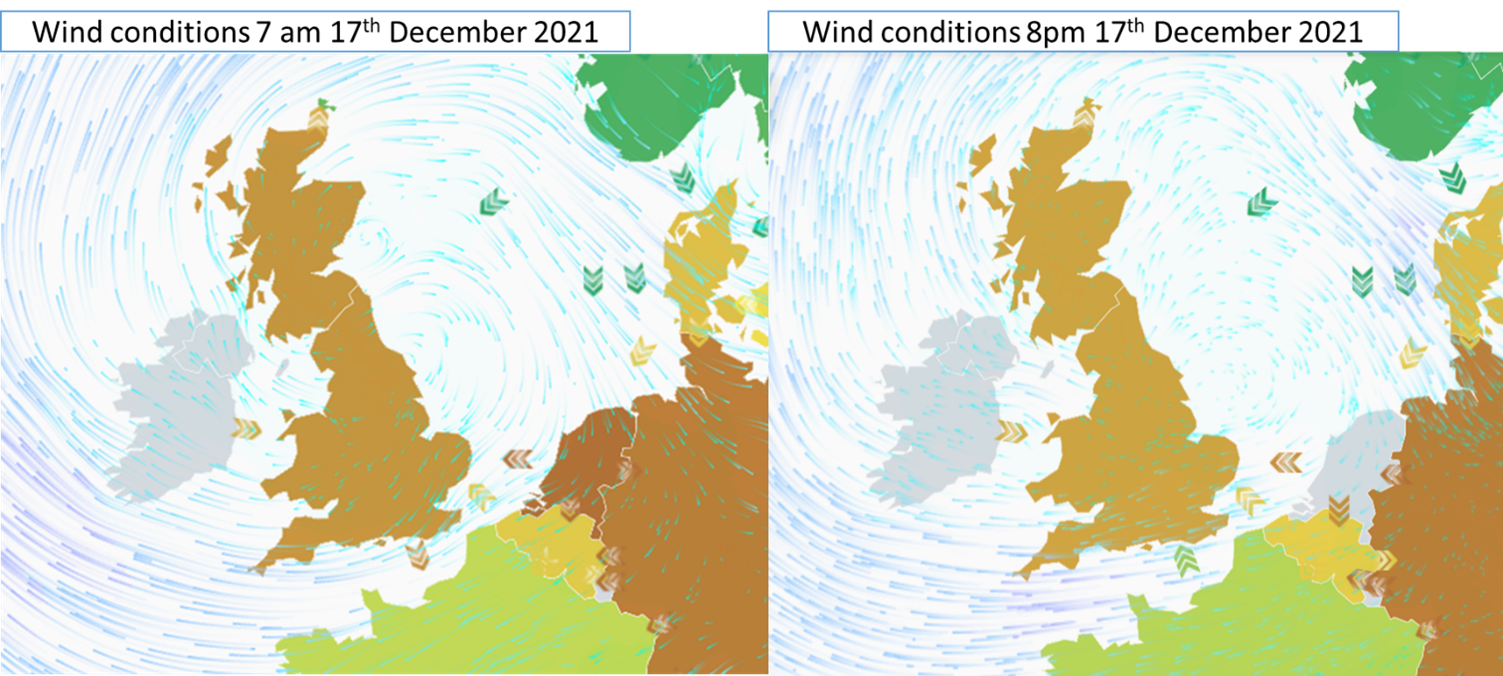

Chart 2 : Wind across the UK and Ireland on 17th December. There was wind – just not where the wind turbines are.

The low wind associated with the area of high pressure is plain to see. It stretches across much of the north sea and also across mainland Scotland and England. Exactly where the majority of UK offshore wind and onshore wind farms are currently located. Wind was also slight off the north Wales and Liverpool Bay sea area, the location of another cluster of offshore wind farms.

The high pressure system was, however, spilling air in an anticyclonic spiral producing higher winds along the English Channel, across the Celtic Sea and Fastnet sea areas, across to southern Ireland, up through the western isles and the north of Scotland. Not gales, but a range of easterly and south-easterly Beaufort force 4 to 6 (11-27 knots), according to the shipping forecast. A force 4 wind isn’t exceptional and equates to a mean wind speed of 7 m/s. Force 6 brings that mean wind speed up to 12 m/s, ideal for wind generation.

Right now there are about 11 GW of offshore windfarms in operation in British waters. The UK government’s target is 40 GW by 2030 and by 2035 we will need around 55 GW to meet the UK’s carbon reduction commitments. We will also need significant investment in interconnectors and energy storage.

It would be interesting to model, on a weekend like 16th to 19th December, what difference it would make to have, for example, 20 GW of this capacity located across the English Channel, Celtic and Irish Seas and off the west and north coast of Scotland. Our premise is that a more diversified wind portfolio would have helped to balance the energy system reducing price volatility and the dependency we had on gas and electricity imports.

We could then go further. Look again at the chart, at the wind across southern Ireland and North West France. High wind conditions also extended down the Bay of Biscay to north west Spain. This is not by chance, a very high pressure system in north west Europe is bound to cause higher winds at its periphery as air is sucked out to lower pressure areas. There is a strong case therefore that UK energy resilience could be enhanced by taking advantage of different weather windows, by the development of wind farms across Ireland and down the western seaboard of Europe, enabled by new interconnector links between Ireland, Wales, southwest England and France. A western corridor of energy generation to balance the concentration now seen in the east.

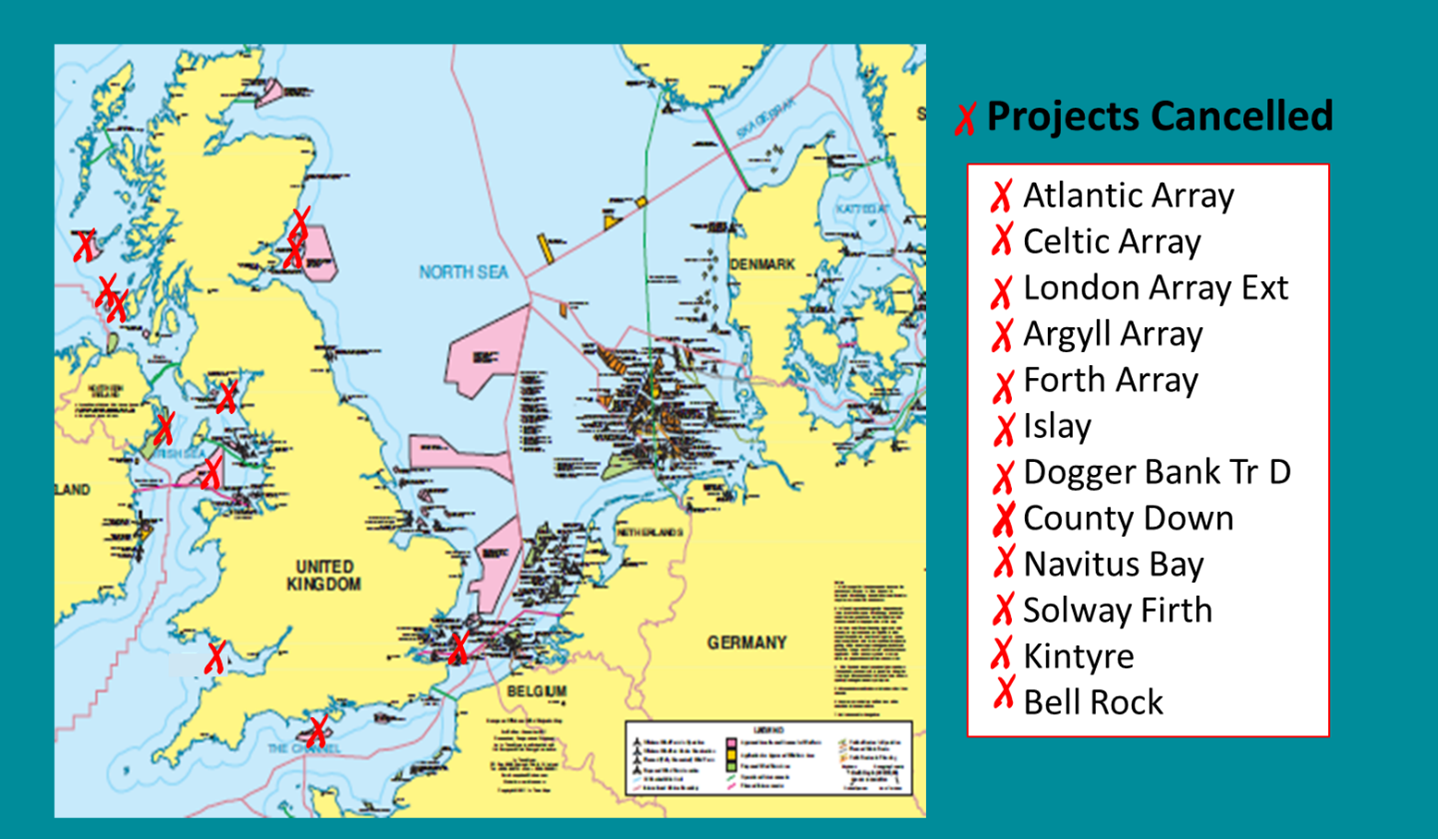

Chart 3 : There has been a dearth of wind projects on the western seaboard, but this is about to change.

Chart 3 is a little out of date, it doesn’t show the recent The Crown Estate Round 4 lease areas, Celtic Sea or the Scotwind areas. What it does show is the concentration of both UK and EU projects in the southern north sea, and the projects that have so far been cancelled on the western seaboard. The three largest projects, Navitus Bay, Atlantic Array and Celtic Array, would have added over 5 GW to the UK offshore windfarm fleet.

The reason these windfarms were cancelled are varied. A common theme is that they all faced logistical and technical challenges of deeper water, difficult ground conditions and/or distance from main manufacturing hubs. Developed before floating wind came to the fore, perhaps they were slightly ahead of their time?

In the case of Navitus Bay, the project probably was viable, but fell at the last planning hurdle with, what must be considered now, a very short-sighted decision by the Secretary of State to reject the application. Atlantic Array faced technical challenges but was probably scuppered, in the end, by RWE’s poor financial results in 2013 and their decision, under intense shareholder pressure, to cut investment to protect its balance sheet.

The underlying problem faced by these developers was that, under the Contract for Difference (CfD) subsidy scheme, each project would have to bid its lowest price to obtain a subsidy in what was becoming an increasingly competitive auction. Unfortunately the CfD scheme does not recognise the value of diversity or its system benefits. It’s a straight auction in which all electrons are considered equal and the cheapest bid wins. This greatly favours the lowest cost projects, inevitably those in shallow waters and those clustered close to manufacturing/assembly hubs, for example, in the north sea.

Nor, under the current CfD arrangement, can there be any market upside for producing energy at times shortage and very high wholeprices. Under the negative subsidy rule, if the wholesale reference price is above the CfD strike price, the generator must pay excess revenue back to the scheme. This phenomenon, which helps reduce current consumer bills, is becoming increasingly common for onshore, and newer offshore, generators, as our previous post explains.

Floating wind – new opportunities

The failure of previous projects in the west is now largely water under the bridge. Floating wind technology has introduced a completely new opportunity to build projects in deeper water and further from shore. This has in turn brought renewed developer interest in areas like the Celtic Sea, around Ireland and northern Scotland. It is also noteworthy that this new wave of developers includes several oil majors who are now eager to join the offshore wind challenge.

Regen was especially excited to welcome Crown Estate’s recent decision to accelerate the development of floating wind in the Celtic Sea with new leases of up to 4 GW to be built by 2035.

Alongside these offshore wind projects, there is also interest in investment in grid and port infrastructure, and in the interconnectors that could provide an energy link from the Island of Ireland to Great Britain and on to western Europe. These are exciting developments that promise to bring jobs and regional economic benefits as well as helping the UK achieve net zero.

The problem remains, however, that, although floating wind has been allowed to compete in the less established technology “pot” in the current 4th CfD round, as the policy now stands future CfD auctions could force floating wind projects to compete with lower cost fixed seabed projects in the north sea. Without the potential for a market price upside, because of negative subsidy payments rule, the CfD mechanism does not seem to be ready to support large scale investment in the west.

This has been recognised by UK government, and by the devolved governments in both Scotland and Wales who have called for a CfD rethink. There are a number of options that could be adopted:

- The most obvious option is to keep floating wind within the less established technology pot, or with its own separate CfD budget, so that it does not have to compete with fixed bottom wind until cost parity is reached.

- Regionally-based CfD auction rounds have also been suggested that would support a range of renewable technologies, including onshore and offshore wind, marine and solar, in geographically focused areas that will also benefit from economic regeneration.

- A CfD uplift could be calculated, allowing projects that are calculated to add to the UK energy diversity and reduce system costs to receive a premium above the auction strike price. Similarly, the Capacity Market could in the future be used to channel additional support for projects that provide additional resilience benefits.

- Instead of the current negative subsidy payment rule, requiring generators to pay back all excess revenues above their strike price, a form of risk and revenue sharing could be adopted allowing generators to retain higher levels of revenue when wholesale prices are high. This would mirror, and offset, the current downside risk generators face when CfD payments are withdraw at times when wholesale prices are negative.

Whatever the options, something will need to be done to ensure the UK fully exploits the opportunity of expanding wind in the west.

Author: Johnny Gowdy

Johnny Gowdy is a director at Regen. His 30 years of experience working in energy industry has taken him from the oil and gas sector to renewable energy and decarbonisation. His oil and gas experience was gained in supply chain consultancy where he supported clients in oil production, and the development of the hydrocarbon supply chains covering the manufacturing (refining), supply and distribution of oil products.

Johnny Gowdy is a director at Regen. His 30 years of experience working in energy industry has taken him from the oil and gas sector to renewable energy and decarbonisation. His oil and gas experience was gained in supply chain consultancy where he supported clients in oil production, and the development of the hydrocarbon supply chains covering the manufacturing (refining), supply and distribution of oil products.

Regen is a not for profit centre of energy expertise and market insight whose mission is to transform the UK’s energy system for a net zero carbon future.

E: jgowdy@regen.co.uk

Look out for our recent insight pieces

This insight paper is part of a series that Regen has produced to explore the role that offshore wind and other technologies could play in a future net zero energy system.

- Building the hydrogen value chain

- A decade to deliver the 40 GW target and the Offshore Transmission Network Review

- Negative subsidies – the advantage of betting on low cost renewables

- Good news for interconnectors

- The offshore wind pipeline explored

- Offshore wind lease round 4 and the rise of big oil